I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more

No, I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more

Well, I try my best

To be just like I am

But everybody wants you

To be just like them

They say sing while you slave and I just get bored

I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more

From Maggie’s Farm by Bob Dylan

Copyright © 1965 by Warner Bros. Inc.; renewed 1993 by Special Rider Music

(Read more: http://www.bobdylan.com/us/songs/maggies-farm#ixzz2w2uoNmHA)

YouTube routinely delivers random advertising for a variety of products against artist videos (either the “official” video or user generated versions of the artist’s work). This means that artists have lost control of a significant marketing restriction that was hard won over years of incremental contract negotiation: Artist approval over the association of their music with products in commercials or endorsements.

It’s important to note that YouTube and iTunes made a choice. iTunes decided to get into the digital distribution business and still accounts for the bulk of digital revenue. iTunes allows artists to charge a price for their music. This indicates a confidence in the iTunes offering–we have these goods and we expect you to buy if you want to engage with us.

What’s important to iTunes is attracting fans who are both interested in music and who want to engage in some commercial transaction with the artist and with iTunes. If you isolate iTunes as a business (separate from Apple), iTunes only makes money when the artist makes money. In a significant way, iTunes interests are aligned with the artist.

YouTube did not make this choice. YouTube instead adopted the antebellum economy of Web 2.0:

- free labor (also known as “user generated content” from users or seeders employed by YouTube who create videos and upload them)

- free labor in the form of YouTube’s exploitation of traffic driven to YouTube by artists promoting their higher value recordings, which is accelerated by

- YouTube’s essential monopoly control over online video content through Google’s subsidizing YouTube’s growth in the form of actual cash subsidies from its monopoly search business (essentially extending its effective monopoly of search into the video search vertical)–meaning that fans almost always go to YouTube to search for videos or are driven to YouTube in a Google search for videos

- only compensating artists in the form of a revenue share for advertising sold against the artist’s videos from whatever source derived, and

Selling advertising against YouTube search results that YouTube does not share with anyone.

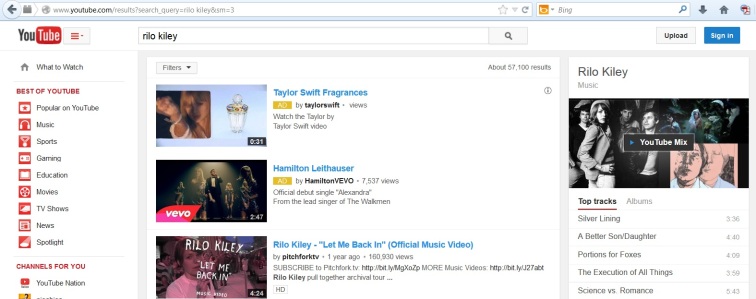

In this example, a YouTube search for “rilo kiley” returned an ad for Taylor Swift fragrances and an ad for another artist’s video on Vevo (which is another service that is partly owned by Google and some major labels, but that is totally dependent on YouTube to operate). Rilo Kiley then is used to promote the sale of products and the artist Hamilton Leithauser, who probably has no idea that Rilo Kiley is being used to promote his record.

So in many important ways, YouTube is the polar opposite from iTunes.

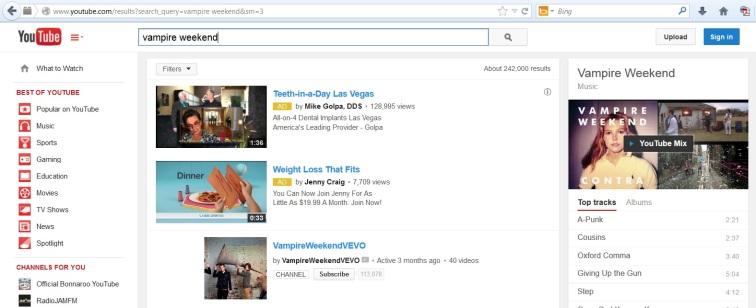

In this example, a YouTube search for Vampire Weekend returned ads for “Teeth in a Day Las Vegas” and Jenny Craig weight loss centers.

It must be said that there is probably a 90% probability that the only way that “Teeth in a Day Las Vegas” and Jenny Craig could get their brands associated with Vampire Weekend is through the charlatans at YouTube for YouTube’s profit under its antebellum economy.

But nobody asked Vampire Weekend or Rilo Kiley or any other artist who drives traffic to YouTube whether they like it or not. And if for some strange reason these artists agreed to allow their music to be used to promote “Teeth in a Day Las Vegas”, it would be at a significant fee–that they would not share with YouTube.

So even if the artist decides not to “monetize” their video on YouTube, YouTube will monetize their videos in video search results.

It is in this context that cellist Zoë Keating makes this thoughtful comment:

Until 2013, I always made a point of not monetizing videos that are live concerts (like those for Wired or ABC Radio National or Chase Jarvis) or 3rd party placeholder music videos….because I wanted the viewers to experience the music. I didn’t want them to see ads, especially ads for things I don’t support, like Doritos. Everyone seems gung ho to embrace advertising but I would like people to see LESS ads, both because I think they make an experience unpleasant and because I want the entire world to consume less stuff (that goes for my merch too. I’m happy to sell you a digital download but I don’t want to sell you a tshirt). Until Youtube allows me some control over what is slapped on my music, I don’t think I want advertising on it. [emphasis mine]

Zoë is articulating a view that I hear from artists a lot–why are we forced to take a share of advertising that we aren’t asked to be associated with and have our videos posted on a service that will use our work regardless of whether we want it to be there. Unless of course the artist spends hours of uncompensated time dealing with YouTube’s byzantine content management system which independent artists rarely get access to anyway.

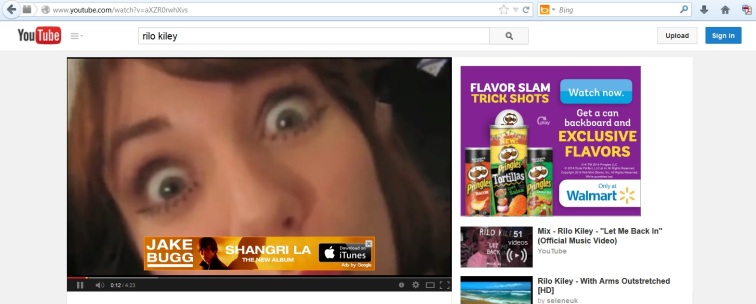

For example, here’s a screen shot from Rilo Kiley’s Let Me Back In video, loaded up with advertising–an ad for Jake Bugg, Pringles and Walmart. I seriously doubt that Jake Bugg has any idea that Google ads are using Rilo Kily’s videos to sell his records, and neither Rilo Kiley or Jake Bugg had any idea that their names or videos would be associated with the sale of hyper-processed potatoes heavily laced with fat and salt, aka Pringles.

What’s the answer? One is the same as it has been ever since YouTube began–stop taking without asking. And for the organized music business–stop letting them do that or put more restrictions on YouTube’s “monetization” of licensed videos.

Understand this: The Web 2.0 antebellum economy is designed for one thing and one thing only and that is to enable incumbent gatekeepers like YouTube to extract as much value from artistic works as possible while paying the creators as close to nothing as possible and while paying nothing to the users who create and upload the “user generated” clips.

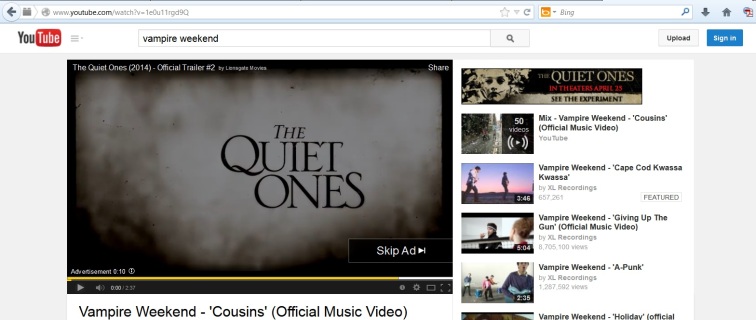

Vampire Weekend’s official video for “Cousins” was monetized with ads for The Quiet Ones horror movie–maybe because of the “vampire” keyword? I doubt this is what either Lionsgate or Vampire Weekend had in mind.

Zoë Keating has never made a music video, yet she has to answer many of these questions. If you ask me, that’s because artists are essentially forced to participate in YouTube due to the extreme lack of control over the service.

Lastly about Youtube… I’ve never made a music video. Maybe I will in the future. I know someone from Google recently said at Midem that “the video is the thing”, and the company changed their search results to reflect that. In my case that isn’t actually true. But what outcome do I want? Until the day I make a video should I upload all my songs to Youtube and make placeholder images for them? And if I do, should I stick to my principles and make the experience more pleasant for listeners and forgo the advertising revenue? Or should I sell out for a few pennies, make the experience as unpleasant as possible and accept ads for products I don’t support? I don’t know the answer to that one!

So it’s pretty clear that despite all of Google’s protestations about online tools to help manage content, there’s one tool that Google doesn’t have for the artist who wants no part of the entire YouTube grubbiness. The tool that stops the artist’s work from being made available on YouTube in the first place.

There’s a reason that YouTube executives got booed at MIDEM.

Advertising-financed entertainment, aka the medicine show business model, has always been a race to the bottom in quality. Music on the radio arguably went completely to hell when pandering to national advertiser focus groups took over during the ’90s replacing programming according to local record sales.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Four Nights of Music Rights.

LikeLike

Shouldn’t YouTube (Google) should have an obligation as the ‘distributor’ to ensure ALL rights owners are properly cleared and compensated for the synchronization use of their programming, particularly since they re-sell, re-package and sell advertising based upon it?

If an artist is a devote Vegan… should their art be re-sold without their consent next to Burger King or Taco Bell? Why shouldn’t Google be forced to directly approach the respective artists (not just the labels) to ensure all works are properly cleared and consented? It’s mandatory for physical product licensing to search,clear and compensate the use of recordings BEFORE manufacturing.

Perhaps they can use “Google Search” to find the respective rights holders after first connecting with ASCAP, BMI, and/or HFA? [seriously]

Who is REALLY policing this MASSIVE revenue stream? Just Imagine if $250M is the estimated annual Piracy Advertising Revenue what values are we REALLY being generated by this Monopoly – the World’s largest FREE streaming service that permits cut & paste e-mail and blog links?

@JeffreyBarkin

LikeLike