By Chris Castle

If you followed the Copyright Office request for public comments on the DMCA “notice and takedown” safe harbors, you will probably be aware of reports that a group called Fight for the Future generated 86,000 comments to the Copyright Office in approximately 36 hours. I will give even money that it will turn out that investigation will reveal that most of those comments were fake.

One reason I’d make that bet is because they look fake. Many were anonymous or pseudonymous and there’s really no way to know who or what submitted those comments. And that’s why there’s a question about whether this kind of public comments can be used at all for policy making.

But another reason I’d make the bet is because we’ve seen this kind of thing before–and no one ever checks.

Recall that we were very suspicious of Industry Canada’s use of anonymous public submissions over the Internet in the public “consultation” on copyright reform in Canada held in 2009. For mysterious reasons, Industry Canada bureaucrats charged with administering the consultation failed to implement even the most rudimentary controls to screen or qualify these anonymous public submissions.

Not only did the Industry Canada bureaucracy fail to implement even rudimentary controls over the public submissions, but they also completely overlooked obvious flaws in the submissions themselves—flaws easily exploited by “a dedicated group of like-minded people.”

Unfortunately, then-Minister of Industry Tony Clement was not given the information he needed to realize that his many public statements about the success of the consultation process will forever have an asterisk by them—“*except for the totally gamed online submissions.”

And then there was an incident in 2007 involving an EFF “petition” against the RIAA. When you click on a “see signatures” link you are taken to a page full of 5 or 6 digit numbers all in columns and rows. What was this? There were literally a couple hundred number sequences, like little serial numbers, all arranged in neat columns and rows under the heading “Those Who’ve Taken a Stand Against the RIAA!” like you’re at the Tomb of the Unknown or something (no pun intended). It’s like you would have expected to see names, but instead you see numbers. And when you click on the numbers, the links point you back to the same page you were on when you clicked the link.

I tried clicking a few other numbers and the same thing happens. Then I finally happen to hit on one that actually shows a few names, names like “O. Online Poker”, “T. Texas Holdem”, “P. Poker Rooms”, towns like “Google, CA” (must be Stanford?), “Świnoujście, ME”, “f, MA”, “Beverly Hills, LA”, “Beverly Hills, MI”, Dubai, “SCOTLAND!!, AK”, and my personal favorite “J. Travolta, Los Angeles”. And then there’s “r. little boys” of “George, AL“. No comment.

We could take some advice from Google’s own advertising customers about fakery. Sir Martin Sorrell, the head of the mega-ad agency WPP, says Google won’t even tell WPP or the advertisers themselves. According to a recent article in the Financial Times, Sir Martin “warned Google that unless it improves its efforts to weed out ‘fake views’ of online adverts, marketers will shift their focus back towards traditional media such as press and television.” Sir Martin was reacting to a study that alleged that Google “has been charging marketers for YouTube ad views even when the video platform’s fraud-detection systems identify that a ‘viewer’ is a robot rather than a human being” and Sir Martin stated the obvious conclusion that “[c]lients are becoming wary and suspicious.”

It’s a short hop from fake views of online adverts to fake anything else, including fake signups to a public consultation on regulations.gov.

A process that allows an organization like Fight for the Future to collect submissions of a form letter and then submit them all at once unnecessarily inserts a gatekeeper into the public comment process. But it is the kind of thing you would do if you wanted to avoid anyone collecting the address information on your favorite robots.

The anonymous and pseudonymous “signers” of the Fight for the Future form letter are not that different from a casual online poll. As former Canadian Minister of Industry Clement learned the hard way, online polls or their equivalent do not make for good policy as that system is inherently unreliable.

I’m not the only one who thinks so. Cass Sunstein, then the Administrator of the Obama Office of Management and Budget, issued a memo in 2010 to the heads of executive branch departments and regulatory agencies which dealt with the use of social media and web-based interactive technologies. If the Copyright Office followed the memo’s proscriptions, it would likely rule out the use by the Copyright Office of online form letters such as the Fight for the Future webforms.

Specifically, the Sunstein memo warned that “[b]ecause, in general, the results of online rankings, ratings, and tagging (e.g., number of votes or top rank) are not statistically generalizable, they should not be used as the basis for policy or planning.” Sunstein called for exercising caution with public consultations:

To engage the public, Federal agencies are expanding their use of social media and web- based interactive technologies. For example, agencies are increasingly using web-based technologies, such as blogs, wikis, and social networks, as a means of “publishing” solicitations for public comment and for conducting virtual public meetings.

As one source noted, “[A] million Americans can Digg or retweet [or Reddit] an important blog post, but government officials shouldn’t use that popularity as an indicator of the post’s value. That’s not always a bad thing considering that a dedicated group of like-minded people can game a casual voting system.” Or the Copyright Office’s public comment process–and it must be said that since Regulations.gov hosted the online comment process, that would rule out any other form letter responses to any consultation for the whole of the federal government as hosted by regulations.gov.

And I think Sir Martin Sorrell would agree that there’s no more dedicated group of likeminded people that a bunch of robots. So if you didn’t before, you get the idea about why Mr. Sunstein had reservations about using online petitions to make policy.

Mr. Sunstein—who some might call something of an Internet evangelist—is clearly trying to establish best practices for the U.S. government to allow the government to benefit from the good of using the Internet to further legitimate policy making goals while avoiding the bad. Avoiding the bad includes a prohibition on basing policy decisions on the use of information that is or could be gamed in the formation of public policy by “a dedicated group of like-minded people.” And the gaming can be done before or after the fact, and the “like-minded people” can be outside—or inside—the government.

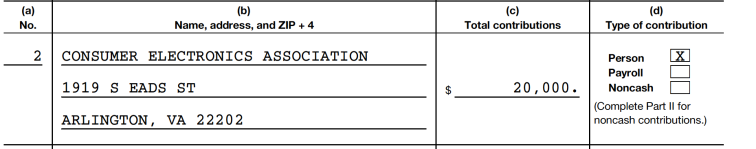

It is not a very large leap to imagine a truly Orwellian world where the government finds that the public supports its policies because it uses information that its anonymized supporters intentionally game or are encouraged to game to produce the desired result. As we noted in Fair Copyright Canada and 100,000 Voters Who Don’t Exist , the legitimate desire by governments to use the Internet to engage with the governed is to be admired. But if the process is selectively managed by bureaucrats with an agenda or groups like Fight for the Future (funded in part by mega-lobbyists the Consumer Electronics Association), it is to be greeted with considerable caution if not outright suspicion.

At least when they count the votes of the dead in Chicago, there was a somewhat real voter registration at some point.

You must be logged in to post a comment.